Introduction

“Legacy code” is a bit of a catch-all phrase developers use to casually refer to any existing code they find themselves working on. While the term is somewhat ambiguous, the impact is all too real. Maintaining years—or even decades—of legacy code demands an outsized amount of developers’ time, increases overhead costs, and inhibits an organization’s ability to efficiently address challenges.

Case in point: Consider last year’s unexpected rush on COBOL programmers. Many government and financial systems still run on COBOL, even though most universities no longer include this half-century-old language in their CS curriculum. This turned out to be a huge problem for several legacy systems, which needed to be updated in response to the COVID pandemic. In order to take advantage of the CARES Act passed by Congress, state unemployment systems needed to be quickly updated to accommodate new rules and a massive influx of recipients. The state of New Jersey, however, found itself stymied through a reliance on a comparatively ancient codebase, which led the governor to publicly plead for COBOL-literate volunteers to update its infrastructure.

The COBOL rush may have been a highly visible case study in the problems of a legacy codebase, but even code based on contemporary languages can cause headaches and heartburn for developers and businesses alike.

As technologies, business processes, and workforces evolve over time, so must the code that supports them. The more complex and sprawling your digital footprint, the more challenging this becomes. Today’s enterprise environments evolve so quickly that as soon as any code is sent to production, it’s already legacy. The only way to avoid the challenges of code is to remove it altogether. In this eBook, we will explore how a new class of no-code development platforms such as Unqork can eliminate the challenges of legacy code.

The consequences of legacy code

Modern-day developers are responsible for scaling functionality across multiple departments, devices, systems, and locations—which means maintaining hundreds of thousands of lines of code built over years, if not decades. Here are just a few of the challenges that enterprises face from an expansive legacy codebase:

Inflexibility

Today's architectures are expansive, disparate, and built on decades of deeply ingrained legacy systems. Most pull data from or push data to external systems, storing data in one system, analyzing it in another, and using another to display it.

Integrating and meshing these systems together with convoluted workflows makes it difficult and expensive to maintain and make updates/changes down the line. Attempting to build and manage within these complex digital systems using code directly contributes to reduced IT productivity. Despite all the iterative-improvement coding tools and organizational approaches, development productivity is getting worse, not better. With one study finding a 20% loss in developer productivity over the past decade.

Technology debt

With limited resources to address every problem in an expansive codebase due to changing technological or business environments, IT teams often must settle for kicking problems down the line with small workarounds. This is known as technical debt. And like all debts, the “bill” will eventually come due.

A very public example of that bill coming due can be found in the recurring effects of the millennium Y2K bug, which is still causing problems two decades later due to short-sighted fixes. Back in 1999, many developers v in the codebase to fix 80% of various systems. This fix treated all dates from 00 to 19 as being 2000 to 2019, while anything beyond the “pivot date” would be considered a previous century. This fix was intended to be a short-term fix, which would surely be replaced before 2020. However, in many cases, the fix never came.

On January 1, 2020, many of the “fixed” systems rolled back to the early 20th century and read the "20" in dates as 1920. Utility companies reportedly produced bills with this incorrect date, and thousands of New York City parking meters rejected credit card transactions because of it. The video game WWE 2K20 also reportedly stopped working that day too, until the developer patched it a few days later. It led to a lot of funny news stories, but for the affected companies, it caused more headaches than laughs—not to mention the costs incurred. One 2018 report estimated that the cost of technical debt that year in the US alone was around a half trillion dollars.

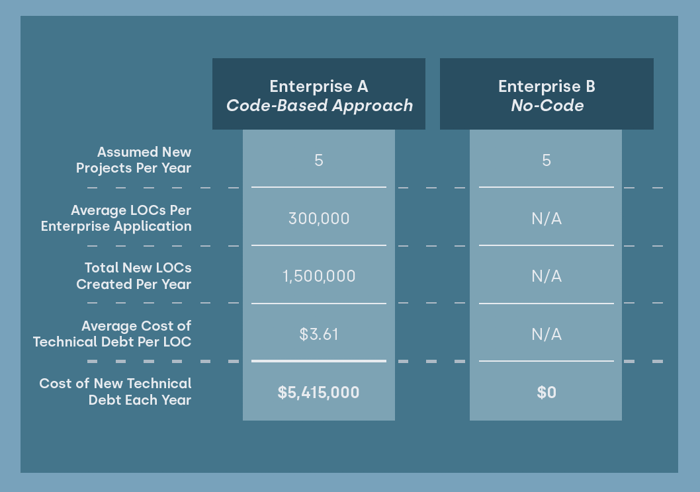

The more code you maintain, the more potential you have to fall into technical debt. One analysis by the CAST Research Labs (CRL) analyzed found that the average-sized application of 300,000 lines of code has over $1 million worth of technical debt. That represents an average debt of $3.61 per line. This can be a huge amount of money over time and place companies at a disadvantage.

No-code vs. technical debt

Consider the plights of Enterprises A and B. They're similar-sized companies with similar goals and are in similar markets. Enterprise A decides to take a traditional code-based approach, while Enterprise B embraces no-code.

Using this framework referenced in this section, we can calculate how much additional technical debt Enterprise A incurs over time by relying on code. Meanwhile, over the course of 5 years, Enterprise B avoids more than $5.4 million in costs to address technical debt. This also means that profits and revenues grow because they can innovate and release new products to stay ahead of the competition.

Maintenance costs

As an organization's digital infrastructure—and its codebase—expands over the years, IT teams are tasked with untangling the web every time a change needs to be made.

Developers will tell you that legacy code takes up a large chunk of their time. One survey found that developers spend 30% of their time maintaining code or an average of 12 hours every week. A Stripe survey found that they spent an average of 17.3 hours every week on code maintenance.

Other studies have shown that developers spend 50% of their time learning the code they have to work with and their employers spend 60% of the development budget maintaining it. No matter how you look at it, that's a huge portion of your IT resources just fixing bugs and dealing with technical debt.

The more time you spend researching old ways of doing things or reaching out to retired developers for fixes to code you're stuck maintaining or fixing.

Add in the new lines of code you add every year, it can add up to several million dollars annually. In the U.S., companies spent $70 billion in 2003 on maintenance and nearly $600 billion in 2018. That's a 7x increase over just 15 years.

Risk

Like those COBOL-based applications or systems that are a honeycomb of applications and networks that are bolted on to each other (like airline management systems). Systems are so interconnected that one small problem can have a cascading effect.

Consider what happened in 2019 when a single piece of safety software grounded flights from at least five airlines, causing planes to be grounded nationally. And the previous week, another software application went down, crippling ticketing and boarding operations for another three airlines.

A sprawling infrastructure is inherently unwieldy, so when you add hotfixes to it that cause new issues, your problems suddenly become very visible to end-users and consumers. You're assured financial damage (according to Gartner, network downtime costs enterprises, on average, $5,600 per minute) as well as reputational damage, which is less quantifiable but can impact your business for years to come. Factor in the 100-to-150 errors most developers average for every 1,000 lines of code (according to Watts Humphrey's book, A Discipline for Software Engineering) and you can see how your codebase is a potential timebomb.

A better way

How can anyone ensure that their code doesn't become too much of a burden to the future? Is there a way to avoid all the refactoring and technical debt to focus on newer technologies that help deliver the right experiences to customers and deliver on the promise of business objectives?

We think there is, and it's called no-code.

The no-code solution

No-code allows companies to build robust custom solutions without writing a single line of code. No-code platforms like Unqork provide a layer of abstraction between developers and the codebase, which means developers focus their attention on configuring application logic rather than dealing with their application's code or syntax.

To be clear, no-code systems do generate code, but users never have to invest any thought or resources into writing or maintaining that code—and that can make a huge difference. Here are a few highly impactful benefits that come from choosing a code-free paradigm:

- Stop producing new code: The most obvious benefit of an enterprise no-code platform like Unqork is that it eliminates the creation of new code that you will have to deal with, which means your team can focus its resources on building value-adding solutions, or maintaining/sunsetting existing legacy code without adding code that will eventually have to be worked on.

- All technical updates are “outsourced”: With no-code, the platform takes care of everything "under the hood" and eliminates the need for you to keep systems up-to-date because the no-code platform provider takes care of everything on the backend. You design the business logic, and the platform handles all the shifting technologies.

- Eliminate human coding errors: No-code eliminates the chances of developer typos when working on the codebase because it removes the need to write any code—and in many cases provides guardrails that proactively avoid errors before they happen. Users create functionality through the visual interface, and the platform handles the coding. The Unqork platform, for example, lets you build your app with configurable components and provides “guardrails'' to proactively guide users away from errors.

- Accelerated development: Building business solutions via a visual configuration-based platform is inherently faster than writing them out in code. This acceleration empowers businesses to hasten time-to-market and time-to-value for new solutions, as well as for any updates down the line. The average enterprise application can take up to a year to go from ideation to production using a traditional code-based approach; with no-code sophisticated applications can be created in a matter of weeks, or even days.

- Flexible workforce: A study by Forrester found that while 74% of enterprises have a digital strategy in place, only 15% seem to have the right skills to deliver it. No-code can help mitigate the global IT skills shortage. While modern programming languages can take a year to learn, and several more to master, platforms like Unqork can be picked up in a matter of weeks. Since the platform handles so much of the “heavy lifting,” companies can use less-experienced developers (or “Creators” as we refer to them at Unqork) to handle routine tasks, while more senior developers can concentrate on applying their experience in more value-additive ways.

At Unqork, we believe the future of software development is based on your business and the people in it, not the code you create or maintain. We believe in using legacy code for good and preventing you from creating more in the future. Want to learn about how to transition your business from legacy code to no-code? Get in touch to see how easy it can be.

The no-code solution

No-code allows companies to build robust custom solutions without writing a single line of code. No-code platforms like Unqork provide a layer of abstraction between developers and the codebase, which means developers focus their attention on configuring application logic rather than dealing with their application's code or syntax.

To be clear, no-code systems do generate code, but users never have to invest any thought or resources into writing or maintaining that code—and that can make a huge difference. Here are a few highly impactful benefits that come from choosing a code-free paradigm:

- Stop producing new code: The most obvious benefit of an enterprise no-code platform like Unqork is that it eliminates the creation of new code that you will have to deal with, which means your team can focus its resources on building value-adding solutions, or maintaining/sunsetting existing legacy code without adding code that will eventually have to be worked on.

- All technical updates are “outsourced”: With no-code, the platform takes care of everything "under the hood" and eliminates the need for you to keep systems up-to-date because the no-code platform provider takes care of everything on the backend. You design the business logic, and the platform handles all the shifting technologies.

- Eliminate human coding errors: No-code eliminates the chances of developer typos when working on the codebase because it removes the need to write any code—and in many cases provides guardrails that proactively avoid errors before they happen. Users create functionality through the visual interface, and the platform handles the coding. The Unqork platform, for example, lets you build your app with configurable components and provides “guardrails'' to proactively guide users away from errors.

- Accelerated development: Building business solutions via a visual configuration-based platform is inherently faster than writing them out in code. This acceleration empowers businesses to hasten time-to-market and time-to-value for new solutions, as well as for any updates down the line. The average enterprise application can take up to a year to go from ideation to production using a traditional code-based approach; with no-code sophisticated applications can be created in a matter of weeks, or even days.

- Flexible workforce: A study by Forrester found that while 74% of enterprises have a digital strategy in place, only 15% seem to have the right skills to deliver it. No-code can help mitigate the global IT skills shortage. While modern programming languages can take a year to learn, and several more to master, platforms like Unqork can be picked up in a matter of weeks. Since the platform handles so much of the “heavy lifting,” companies can use less-experienced developers (or “Creators” as we refer to them at Unqork) to handle routine tasks, while more senior developers can concentrate on applying their experience in more value-additive ways.

At Unqork, we believe the future of software development is based on your business and the people in it, not the code you create or maintain. We believe in using legacy code for good and preventing you from creating more in the future. Want to learn about how to transition your business from legacy code to no-code? Get in touch to see how easy it can be.